I am a huge advocate of fringe theatre: it is a platform with no boundaries on subject matter or performance style. In my tenure as a reviewer for London Pub Theatres I have seen plays that I wish to erase from my memory, but I have also seen some of the most thought-provoking, brave, original and thrilling plays in my life to date. Every time I take my seat in a pub theatre and the lights go down I have a joyful sense of anticipation because what I’m about to see could be sheer brilliance. I have often left a mainstream theatre feeling disappointed but have never walked away from a fringe play without feeling either exhilarated and inspired; challenged and disturbed (or all four). Fringe productions make you think and that is, in my opinion, what art should do.

Fringe is the cornerstone of London’s theatre scene and is growing at an exponential rate. In London alone, there are over 47 fringe venues and an array of fringe festivals giving voice to those normally ignored by mainstream theatres.

In London, the division into West End and Off-West End, doesn’t fully realize the diverse nature of theatre. The Off-West End category includes such mainstream venues as The National and the Old Vic as well as fringe. For me, fringe is synonymous with pub theatres and pop-up venues: smaller; intimate performance spaces that are more immersive than traditional theatres.

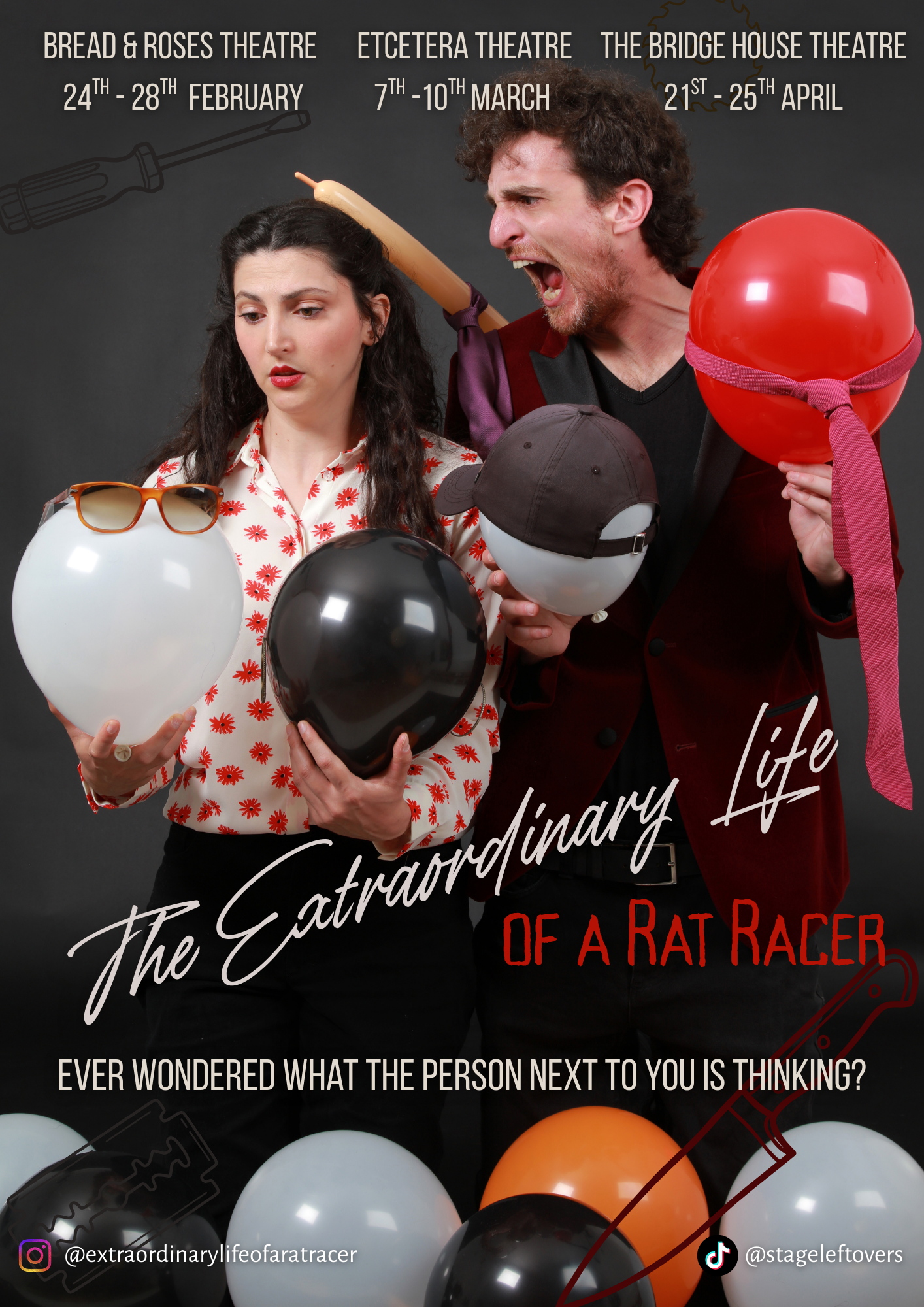

Pub theatres frequently have runs of re-discovered plays, new writing or contemporary plays and separate into two categories: Theatres which produce in-house shows and are a receiving house for visiting companies selected by a rigorous and competitive process. These also offer shorter runs to more experimental productions. The other category includes pub theatres which don’t curate the shows but hire out the theatre space to individuals and theatre companies, leading to a varied standard, but providing a fantastic opportunity for newcomers entering the industry

Fringe is a relatively new concept and stems from the 1940’s when several theatre companies, which were rejected by the Edinburgh International Festival, decided to show-up anyway and performed at smaller venues around the main festival. Journalist Robert Kemp coined the term in an article, “Round the fringe of official Festival drama there seems to be more private enterprise than before.”

The Edinburgh Fringe Festival, as we know it now, was founded in 1947 but the term ‘Fringe Theatre’ wasn’t widely used until the debut of ‘Beyond the Fringe’ in Edinburgh in 1960. The Traverse Theatre

in Edinburgh was one of the pioneering fringe venues co-founded by John Calder, Jim Haynes and Richard Demarco in 1963. It created experimental and mixed media work seeking to invoke the spirit of the Edinburgh Festival all year round. Charles Marowitz and Thelma Holt followed suit and opened the Open Space Theatre

in London in 1968. Their productions included work by young British writers, amongst them David Hare, who wrote plays that were politically motivated and addressed contemporary issues, attracting audiences due to their boldness and alternative outlook.

Despite its origins fringe isn’t just a British phenomenon – it’s a global sensation. Europe has “free theatre” groups, Japan has Shogekijo

(Little Theatre), America has Off-Off-Broadway

and Africa has the National Arts Festival. Its appeal is universal.

Fringe is a breeding ground for raw talent. It’s where some of our best-loved writers and performers, such as Victoria Wood

and Alan Ayckbourn, got their start, allowing them to develop and perfect their skills. It’s also a hotbed of upcoming comedy talent. Most comedy personalities that dominate our TV screens today started out playing fringe venues: Catherine Tate

and Lee Mack

took a sketch-show to the Edinburgh Festival before becoming household names; David Mitchell

and comedy partner Robert Webb

played Theatre 503, then went on to Edinburgh which led to them being talent spotted. Roisin Conaty

played pub theatre venues such as The Canal Café, honing her comedy skills before graduating to the Edinburgh Festival.

World renowned comedians, like Eddie Izzard, were also regular staples of the Edinburgh Festival for years before going on to global success. The list of previous winners of the Perrier Award

(now renamed The Edinburgh Comedy Awards) reads like a who’s who of British comedy. Recipients include Stephen Fry, Frank Skinner, Lee Evans, The League of Gentlemen, Harry Hill, Noel Fielding and Sarah Millican.

Fringe is also responsible for some of the biggest hits to transfer to the West-End. ‘The Play That Went Wrong’ for instance originated at The Old Red Lion Theatre

in Islington and without that initial support would not have gone on to critical acclaim and its raging success. Fringe takes chances. Ironic that the unsubsidised theatres are more daring in their programming than the mainstream theatres which can afford to take a chance on original work rather than dusting off another version of Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde or Noel Coward. There’s nothing wrong with reimagining the classics but given that there have been 17 productions of Macbeth so far this year (as of May 2018) in mainstream theatres across the UK, surely, it’s a sign that the time has come to commission new work rather than just regurgitating the classics.

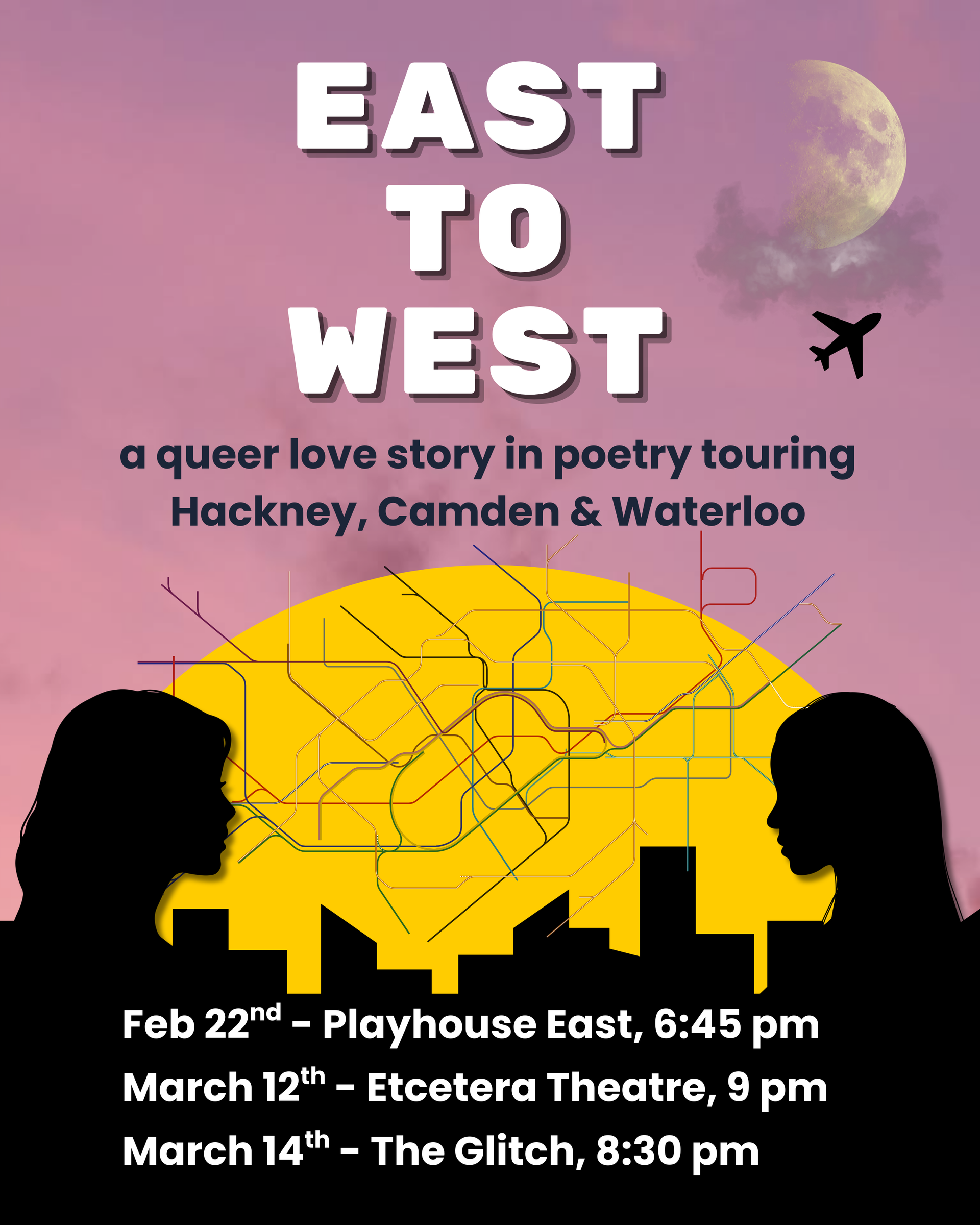

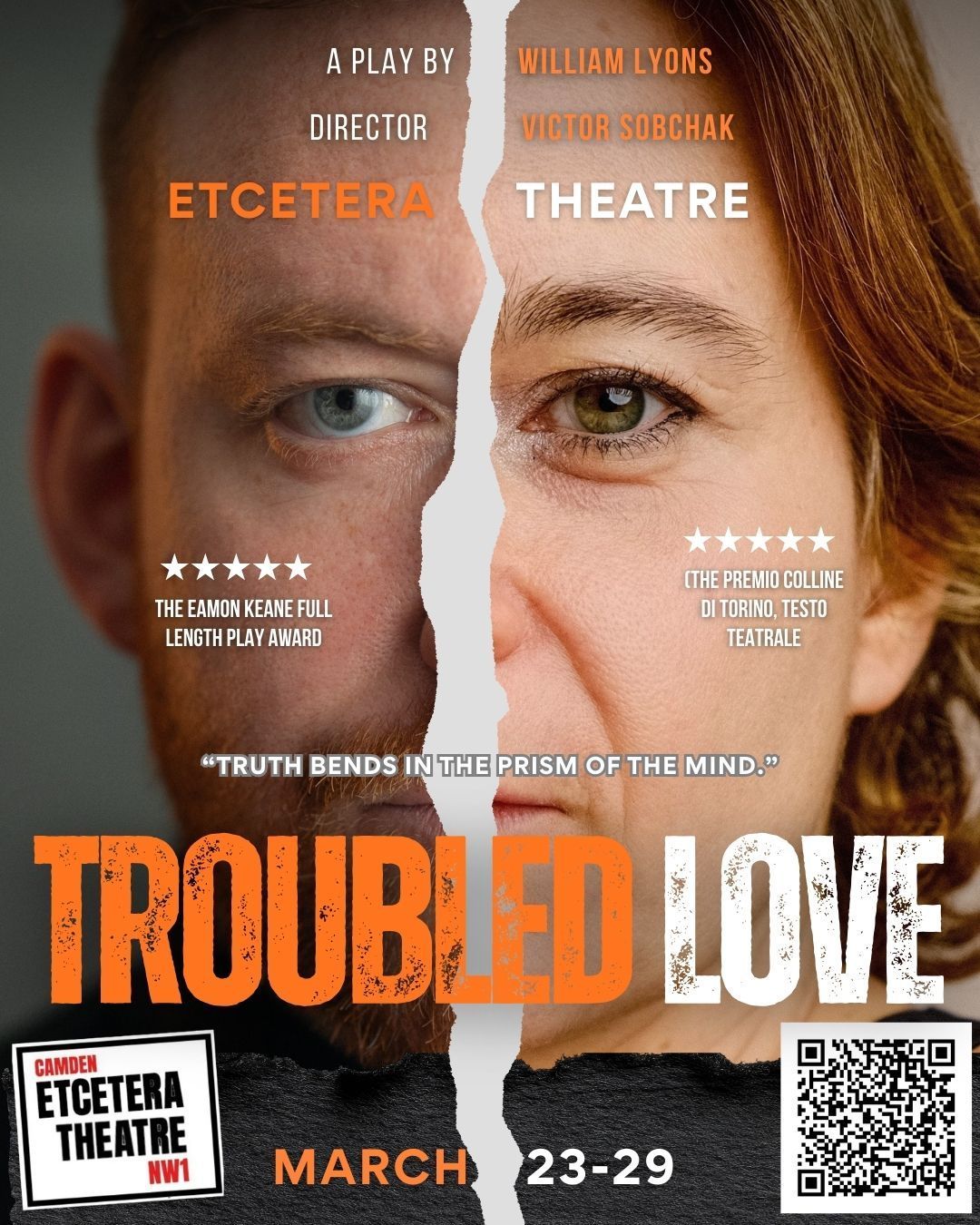

The forthcoming Camden Fringe Festival

(August), which sprung up as an alternative for those unable to attend the Edinburgh Festival, has now become a high-point on London’s theatre calendar in its own right. It’s a place for many artists and companies to perform previews of their Edinburgh shows and test their material. At present the Camden Fringe boasts over 22 venues and over 270 productions performed in the course of one month, showcasing a variety of styles including: classic theatre; magic; poetry-performance; stand-up; opera, dance; circus; improv; puppetry; musicals and mentalism (mind-reading).

There are new fringe festivals popping up all the time and they’re proving a popular way to entice audiences into the theatre, by catering to all different tastes and interests. There’s a festival for everyone from genre themes, such as the annual ‘London Horror Festival’ (Old Red Lion

and elsewhere) to politically flavoured festivals, such as the ‘Outcast Festival’ (The Bread & Roses Theatre) which focuses on telling the stories of marginalised groups, 'Playmill' festival of new work (King's Head Theatre) and Voila, a festival of European work across linguistic boundaries (Etcetera Theatre

and elsewhere).

Fringe festivals encourage new writing, diversity, support up-and-coming theatre companies and make it easy for audiences to attend – with them you’re able to book in advance or buy a ticket on the door on a whim. Fringe venues also offer discounts if you book more than one show or one night of a festival. Everything about them is designed to attract an audience. Another advantage is that, unlike west end productions, performances tend to be an hour long, which allows audiences to attend multiple shows in a single evening.

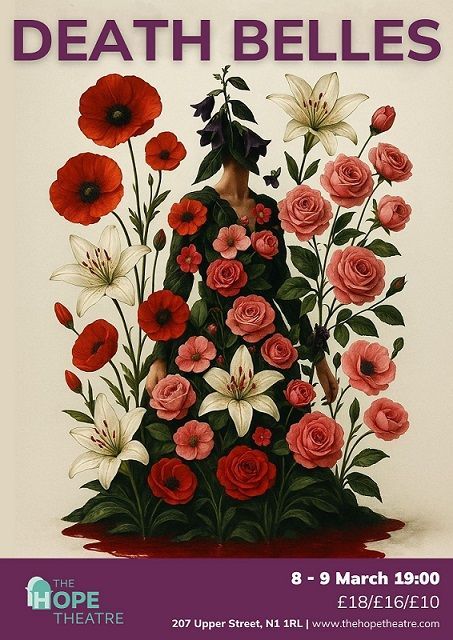

Festivals also provide an opportunity for successful shows to be picked-up for longer runs by established theatres. For example, after a short run at the Camden Fringe a play may transfer to The Vaults festival for several days. The shows that garner good reviews at these events are more likely to be offered lengthier runs at highly respected theatres such as the King’s Head, Theatre 503

and The Hope, amongst others.

Fringe’s adventurous, interactive and no-holds-barred approach has made it not only a viable alternative to mainstream theatre but in many ways more edgy, experimental and innovative. With virtually no budget a lot of inventiveness goes into ways to get around expensive sets, props and special effects. The results can be startling, incredibly creative and breathtakingly ingenious.

Another facet of fringe I enjoy is the variety of venues, each with its own unique backstory and outlook. Some venues are steeped in history such as The Rosemary Branch Theatre

in Islington which was once a Victorian music hall with the likes of Marie Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin treading its boards. There’s also the novelty of newer venues with flexible staging that can be adapted to fit every production, such as The Bread & Roses Theatre

in Clapham. I have never been to The Bread & Roses and seen the same seating arrangement twice. Given the limited space they endlessly utilize it in clever and inventive ways. Others have a collaborative outlook, such as the Jack Studio

(known affectionately as Brockley Jack) in south London, which offers new companies a space to develop their work together with whatever production is being created by the in-house team.

According to Alistair Smith, editor of ‘The Stage’: “London theatre is better attended than Premier League football and takes more at the box office than London’s cinemas.” This is surely a trend of which we should take note. People want to be entertained, want originality and are turning to fringe theatre for it. The Prague Fringe Festival

is a case-in-point. Founded by Steve Gove in 2002 and modelled on the Edinburgh Festival, it’s the largest and longest-running English-speaking theatre festival in Europe. With a turnout of 400 people in its first year it now draws an audience of 6000 per year. That’s an increase in attendance of 1500% percent.

The joy of fringe theatre is its adventurousness and inclusiveness – it has something for everyone, regardless of age or walk of life. Fringe is not only a viable alternative to mainstream it’s setting the benchmark. So, do yourself a favour, attend a fringe festival this year, you won’t regret it.

@July 2018 London Pub Theatres Magazine Ltd

All Rights Reserved