A shifty character in a dodgy hat and a suit of clothes that haven’t seen a wash in few weeks too many scuttles through the London streets around the Rose Theatre, eyes darting from side to side for fear his creditors will lay eyes, and then heavy hands, upon him.

He’s out of cash, again, his playwright’s too distracted by love, again, to finish his script, and the Lord Chamberlain’s just closed all the playhouses, again, because of the plague. In other words, it’s business as usual in the world of the theatre of the 1580s for the impresario Mr Philip Henslowe in Tom Stoppard’s Shakespeare in Love.

And for all of us who, 440 or so years later, make any part of our living from the drama, Mr Henslowe’s plight remains the reality, even if his boundless optimism that all will turn out well before he has his feet burned and his nose cut off can be hard to summon right now.

“How will you pay” asks Mr Fennyman. “I don’t know” says Henslowe “It’s a mystery”.

Somehow it does all turn out for the best in Henslowe’s best of all possible worlds, and the cash-strapped theatre staggers on for another year to another crisis. After all, Shakespeare managed to bang out King Lear while he was locked down during one of his plague years (a mixed blessing, I grant, for all those fourth-formers who’ve had it imposed on them when too young to care for blustering old men).

The solution to our own mystery is yet to unravel.

My personal curtain fell on 14 March, half-way through a short run of The Way to a Man’s Heart, my Canadian debut – and thank you, thank you to the splendid Gabriola Players of British Columbia who made it through enough performances to let me put that on the CV and pay for a half-case of claret, already largely and cheerfully consigned to the recycling bin of history.

But what for people as fortunately situated as I am is a sadness and an inconvenience is the barrel of a gun for the vast majority of our fellows who’ve seen their work fall off a cliff, their futures become an empty canvas.

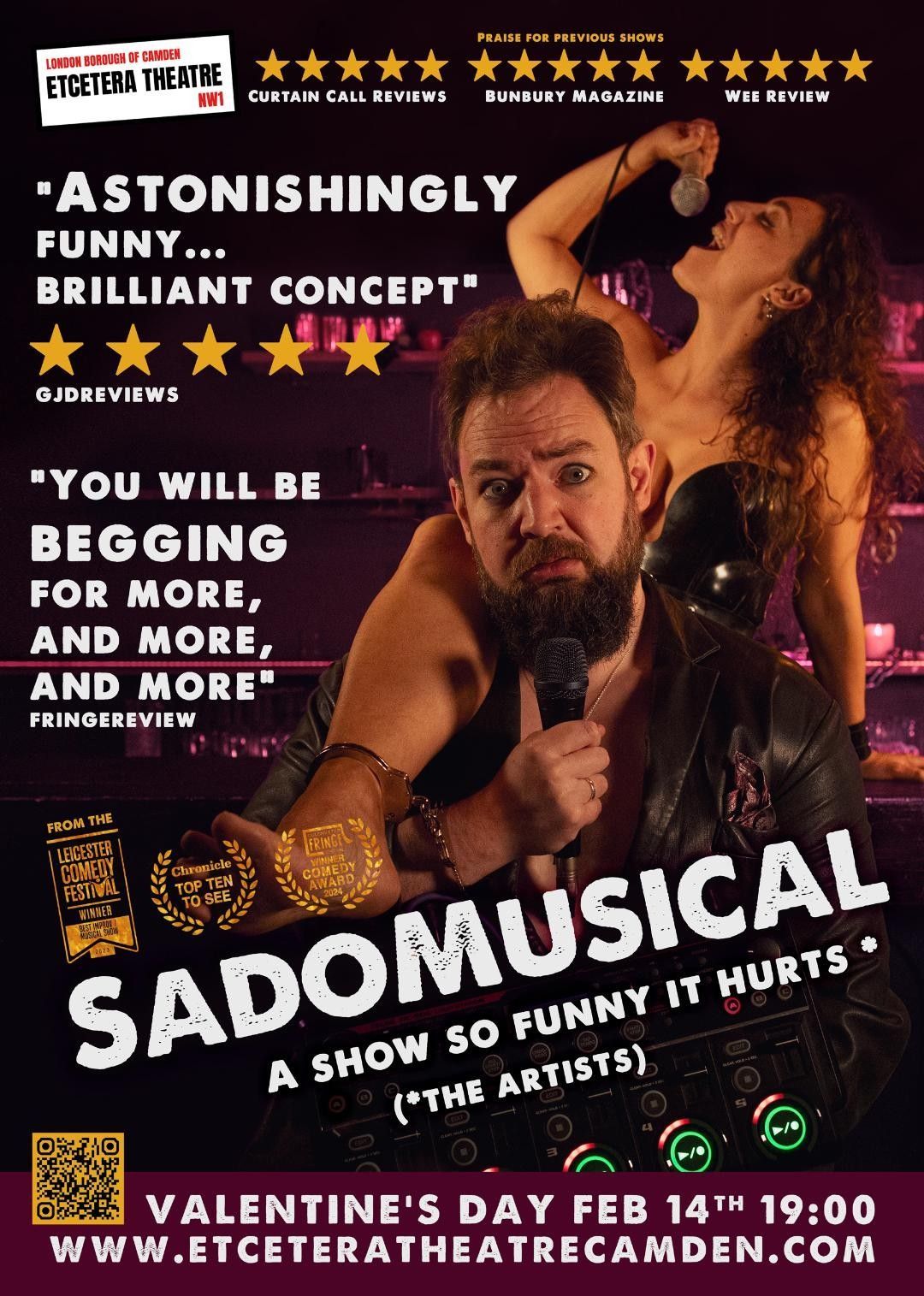

I’ve friends who’ve been furloughed, I’ve friends who’ve been fired. I’ve no idea how the pub theatres that have been the lifeblood of London’s Theatre this last decade and more will be able to get the show back on the road when all this is over.

And how, if they don’t, the bigger theatre will find the talent, the actors, the writers, the creatives, the technicians that rep used to feed through the system and that pub now provides on tap.

The outlook’s as bleak as it’s ever been and more than a few of us are probably wishing we’d listened when we asked some seasoned actor for advice and they said “Become a lawyer”.

This crisis, which came on us out of the blue, will be the death knell for some of the pub theatres we’ve grown to love. Some simply will not be able to ride the months with no show, no audience, and above all not even the income that somehow kept them afloat in ‘normal’ times.

Theatre has, of course, coped in earlier times with unexpected closure – in the plague years of the 17th century for example, travelling companies were able to get out of the bigger towns and cities and set up in local areas, an option available neither legally nor culturally in a 21st century that’s long left behind the vagabond players of old and that might prefer home movie night with Deliveroo to a draughty heath or village hall.

In the last 100 years or so, the two World Wars had different effects on theatre – in the first, the shows stayed open, almost as a patriotic duty to demonstrate that fear would not drive us into the dark, even though there were Zeppelin raids that disrupted performances, for example at the Old Vic. It’s a remarkable fact that audiences none the less kept turning up, and sometimes sat on through the raids until performances resumed on the all-clear.

The ‘Spanish’ flu that followed that war (it’s unlucky for Spain that it carries the title just because it was more open than anyone else about the massive death rates being suffered from 1917 as a pandemic swept most of the world) posed a similar challenge to our own coronavirus.

Unlike today, there was no order to close the theatres, or much else – and the death toll was far higher than anything we’re imagining right now, which may be a handy reminder that the strictness of what we’re going through does have a purpose.

The Second World War, with far greater air power at the enemy disposal, was another matter again – the injunction to put the lights out did mean quiet theatres, with an order to close them all issued as the war began in September 1939.

“I can’t do anything but act, what is to become of me"

lamented Dame Edith Evans, a sentiment many of us may less histrionically be agreeing with right now. The Government quickly relented to pressure and allowed limited opening, enabling Dame Edith once more to brandish her handbag as Lady Bracknell within a month, with audiences some way off capacity but consistently present.

Bombing raids inevitably meant more temporary closures throughout the war (though the Windmill Theatre famously never closed, offering its popular brand of comedy and smut throughout the emergency).

Since 1945, there have been other disruptions – theatre by candlelight in the three-day week of the early 1970s, closures and reluctant audiences during IRA bombing campaigns in London. Restrictions on movement during the foot and mouth outbreak led to some closures in the early 2000s, and, of course, nothing opened in London the night after the underground was bombed in 2005, though audiences were back, if not in full number, the very next day.

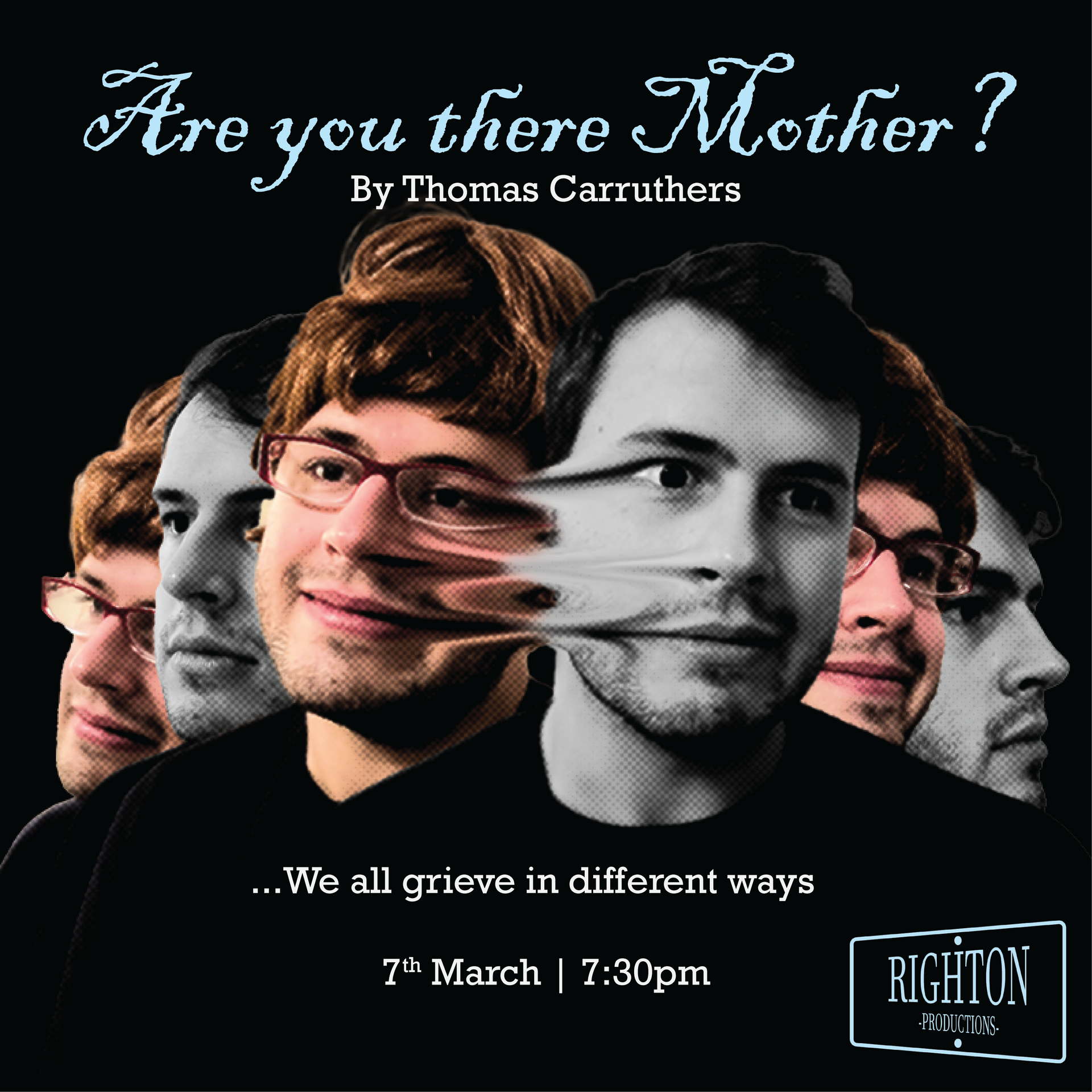

There are actors – and future actors – now looking for any work in any trade anywhere they can find it. There are plays not being written, there are shows that will never be performed, there are careers that will never happen. The road not taken.

There are Government schemes for those furloughed (a maximum £2,500 a month must look attractive to a fair few theatre practitioners), a distant echo, perhaps, of the payments Parliament voted to cover lost earnings for elite acting companies such as The King’s Men in the 17th century.

Without royal or aristocratic patrons these days, though, most theatre professionals are self-employed, and there’s some help for those, too, though the Society of Authors identifies the average earnings of a writer at around £10,500 a year, and how little pub theatre actors earn is anyone’s guess. These schemes are welcome lifelines, but even for professionals who were never in it for the money, not enough to keep the flame alight.

The fear, I guess, is that audiences won’t be back this time – that the risk of human contact and the need for social distancing will glue us to Netflix rather than risk anything from a 50-seater and an experimental two-actor show to a West End spectacle. (And yes, I’ve heard all the jokes now about how my kind of show won’t need social distancing for the half dozen diehards who come watch them).

But theatre will, collectively, if not for every practitioner, every building, survive. Because theatre always does, because the primal need for story – telling it, in words or in actions, and hearing and seeing it told – does not die, even if, at times, it has to be second to our need for food, for a roof, for warmth.

We’re social beasts, we humans, which is why we love stories, and have since our ancestors gathered round a fire in ancient Greece to listen to Homer’s tales of heroes crossing wine-dark seas. We need story, we need human contact, we need tales that touch our hearts even as we rub shoulders with strangers.

We will return to the box office once it’s able to open again. We will queue for over-priced, over-warm white wine, dammit, even as the interval bell rings the fourth time. We will shell out four quid for a programme and forget to read it and leave it under our seat.

We must, in the meantime, take what opportunities we can. We must keep up our skills – as a writer, I can write, even if there’s no-one clamouring for new plays at the moment (in my head, in the glory days before March, they were hammering my door down!) and the month-end royalty statements contain very round numbers indeed.

There’s certainly the space to do it – locked down at home, the desk is bare, the laptop’s waiting, there’s no excuse for indolence. It’s time to remember what that pre-eminent Broadway and West End farceur PG Wodehouse called the essential talent of any writer – to apply a bit of chewing gum to the seat of the chair.

It may be myth, it may be legend (and writers live on making stuff up so let’s go with it), but Victor Hugo is supposed, in order to force himself to pick up his pen, to have ordered his servant to lock him naked in his room so that he couldn’t leave and had nothing to do but write. If that produced the thousand pages of Les Misérables and, distantly, one of the most successful shows in the history of British theatre, then there is something to be said for privation, even if going the full Victor Hugo may not be advisable in the era of the Zoom call to your agent.

If Covid-19 can be the malign metaphorical equivalent of that servant locking us in our rooms, then actors can practice their skills in online readings, writers can write and producers can read and read and read, and plan what extravaganzas the public will need when all this is over and we can breathe again. We can all do the work. The glory’s nice, the money’s essential, the camaraderie of joint production is fun. But the work’s what makes it all worth it, and what drives us to do it, isn’t it?

So there’s space to write, and there’s time to read and learn, and as unkind friends have told me there’s the chance, at last, to prove that I love theatre more than I love pubs. But, of course, being human, we’re never content that what we once dreamed of is given us.

“You’ll have the time of your life” says Lucy, to Geoffrey, her old colleague on the newspaper who’s shortly to retire in Michael Frayn’s ALPHABETICAL ORDER. “Bit of peace and quiet at last”.

“That’s what we all want – a bit of peace and quiet” says Geoffrey. “The only thing we don’t want is a lot of peace and quiet.”

Peace and quiet’s been our lot for 80-plus days now since the theatres closed, and no sign of curtain up again any time soon, even if, we have to hope, the future’s not quite as bleak as it is for poor old Geoffrey.

I can’t think of a single pub theatre that actually uses a curtain, but, metaphor or cliché, it will rise once again.

We’ll have lost friends, talents. We’ll have lost spaces we love. We’ll have lost shows never written or cancelled or swept away in the storm. But there will be new shows, new talents, new spaces. The urge to create is too strong to be destroyed. The plague will lift from all our houses.

“How will you pay”

asks Mr Fennyman, back in Shakespeare in Love again, holding his knife to Henslowe’s nose. “I don’t know"

says Henslowe “It’s a mystery.”

But pay he does. The show goes on.

Read David Weir's article PLAYS SET IN A PUB >

DAVID WEIR is a London-based Scottish playwright. Plays include Confessional (Oran Mor, Glasgow) and Better Together (Brockley Jack, London). Confessional won the SCDA prize for Best Depiction of Scottish Life and Character at the 87th Annual One-Act Play Festival in 2018. Other awards include: the Constance Cox Award and the Write Now Festival Award. Legacy and Better Together were both long listed for the Bruntwood Prize. Lions of England is published by Stagescripts Ltd. Confessional is published by Spotlight Publications.