Hello Alex, Delighted to have this opportunity to ask you about your work. Firstly, you must have heard people describe pub theatres as being small scale theatre. What do you say to that?

I always say designing for the Finborough is a bit like the stage design equivalent of close up magic. In a large venue you can get away with quite a lot due to the distance between the performer and audience, however, at the Finborough you can see the small change being handed from one person to another, you can tell if the stamp on the envelope is period or not and you can read the contents of a letter over an actor’s shoulder (so woe betide anyone who tries to get away with writing blah blah rhubarb). Inevitably you are trying to convey a sense of authenticity on a miniscule budget but it’s great to try and get the details right if you are doing a ‘slice of life’ style of play. The intimacy of the space is actually one of its key assets as there is nowhere to hide. You can wrap the space round the audience and help them to feel they are in the action, rather than passive spectators.

What are your top tips for achieving a successful design in a small space?

It’s the same as designing for any space, and that is to really know that space and try and use its benefits and its limitations to your best advantage. The Finborough has got a good height to it, as it is one of those fine high ceilinged 1860s pub function rooms (I’ve even created two level sets in there on a few occasions now), and it has that lovely D shaped bay window at one end that has provided the spring point for a fair few designs. The Finborough is also quite unusual for a pub theatre space in that it can offer a range of different seating to stage arrangements, all of which I have used over the years. So, one of the key things is to chat with the director as early as possible and try to establish what stage form would work best for the play.

I once had a director who gave me a very detailed description of how she wanted the stage to look and what seating configuration should be used. It was hardly surprising as she had been living with this project a good while before I came on board and naturally you have to fill the vacuum. She looked a bit disappointed when I said that to realise her vision, we would have to reduce the audience capacity by 10 and I would need twice the budget. I then asked her how the piece should feel and for any other thoughts, no matter how left field or apparently inconsequential. My favourite sentences when I’m having a first meeting with a director are the ones when they say ‘I’m not sure what I mean by this, but...’, or, ‘it might sound a bit odd but, I feel that...’, as I can do things with statements like these. I went away and returned with a design completely different to the initial brief and she said ‘Yes, that’s exactly what I wanted!’. But that’s why you employ a designer, to come up with a practical solution and complete that part of the circuit. Some directors are very visually attuned, and we might both scribble all over the sketch pad, which is fine; others less so, which is also fine. Theatre is one of the few arts where you can’t really do everything on your own

Nevertheless, smaller spaces present challenges for set designers. What are some of the problems?

Practicalities such as access and lack of backstage space can be a big challenge. However, this can also force you into inventing some less obvious and more creative solutions to design problems than you might if you had tons of kit at your disposal. Say you need a bed on the Finborough stage… This can pose a bit of a challenge, as you can’t store it off stage as it would take up too much room and it certainly wouldn’t fit through the narrow door anyway.

For the premiere of James Graham’s play Eden’s Empire I had to create an environment that represented a whole range of locations including: The House of Commons, a posh establishment club, parts of Nasser’s Egypt and most troublingly, the two scenes set in the Prime Minister’s bedroom. I couldn’t find a way of neatly fitting the wretched thing in anywhere. Eventually, I concluded that I was trying too hard and that I should pursue the ‘hiding in plain sight’ option. I built the prime minister's imposing Downing Street desk from scratch as, unbeknown to the audience, the whole top could rotate with the mattress and pillows already attached to the underside. James was already experimenting with the quirky almost vaudeville style he has used in many of his subsequent plays, and it got a good audience reaction when the desk top spun round to reveal the bed and Mrs Eden slotted the headboard in to place. It proved a humorous and appropriate metaphor, for even when Anthony Eden is at home in bed, he is still literally chained to his desk!

What is absolutely necessary is to provide enough of an environment for the actor to tell the story and you build the design outward from there. Sometimes it’s the right choice to go for naturalism in our attempt to build a believable world, on other occasions you can go for abstraction or symbolism.

Is there a danger that a set can dominate a play?

I have seen many productions where a set, and quite often the direction, are trying to do a ‘thing’ which is totally at odds with the message, theme and feel that the play is trying to convey. This is not to say that a text can’t be stretched, tested, and interpreted in all manner of different and exciting ways, but I think you have to fundamentally understand the anatomy of the beast you are dealing with before you start surgery. I have to work out the author's intentions, listen to the director’s brief and establish the ground rules of the world I’m trying to create. I might want to break or subvert the rules at some point, but I have to know what the rules are before I subvert them, otherwise the production runs the risk of looking and feeling a bit incoherent. Many audiences won’t be sitting there saying ‘it was the set that done it’, but they will know that something wasn’t quite right, and it becomes an uphill battle for the actors to ‘sell’ the concept.

Sometimes you can legitimately include moments that are entirely about show and impact. When I was designing the European premier of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Me and Juliet at the Finborough, I suggested that it would be fun if a silver shimmer curtain rose up out of the floor behind all the tap dancers at the close of the Act one finale song. Fortunately, the director, Thom Sutherland, agreed and a shimmer curtain attached to a riser bar duly rose out of an upstage floater trap every evening. Noticeable, certainly... Dominating perhaps... But the finale number was called ‘Keep it Gay’!

Is there a lot of science involved in the magic of theatre?

Technically in magic there are only a few basic types of trick and the art rests in the presentation of that trick. Transitions in theatre are similar, in that there are a reasonably limited number of ways you can get from A to B and how you chose to handle these links is every bit as important as the scenes they bookend. In Victorian theatre you just dropped the curtain in, the scenery was changed, and the curtain was raised on a new vista. These days the audience like to see the magic of transition happen in front of them.

I recall a production at The Finborough that presented me with just such a transition challenge. In

The White Carnation by

R.C Sherriff the first short scene happens outside the protagonist’s house. A gust of wind slams the front door and he has to break into his own house through a window. As he climbs through the window, he travels to the same house but in the future. In the original script it was indicated that the first scene was done essentially as a ‘front cloth’ scene. The curtain is then dropped in and the set is changed to the main house interior.

To my mind this completely breaks the flow of the action, so I designed two revolving flats, one which had the front door on one side and a fireplace on the reverse and the other showing both sides of a sash window. This enabled the action to be continuous as the protagonist walked up to the exterior window, tried to open it and in doing so spun the whole flat round so that he was on the outside looking in. He then punched out one of the panels of glass so that he could undo the catch, slide up the sash and climb back on stage and into the sitting room. Taken as a blow by blow account it’s really very simple, however, like all good theatre magic by the time you add sound, music, atmospheric lighting, and of course have an actor like Aiden Gillet performing the part, you end up with a bit of theatre magic.

Looking back at 20 years of designing for the Finborough, which production has been the most demanding of your talents?

I have produced over 30 designs for The Finborough ranging from the mildly over-ambitious to extremely simple. I have recreated World War One trenches up there and a much more up to date army camp in Afghanistan. I have also recreated the backstage world of Moliere’s theatre and a Victorian tiled public lavatory. Every play, no matter how simple, usually has some kind of demanding aspect, but that’s what keeps things interesting.

One of the things that has kept me coming back to the Finborough are the play choices, both from the new writing and the rare revivals strands. It’s exciting to re-imagine epic scale productions that no commercial producer would touch; or quirky, esoteric productions that would never fill a 700-seater but will guarantee getting 50 people a night. This might be the only time this play has been staged in the last 60 years.

Do you have a soft spot for a particular production?

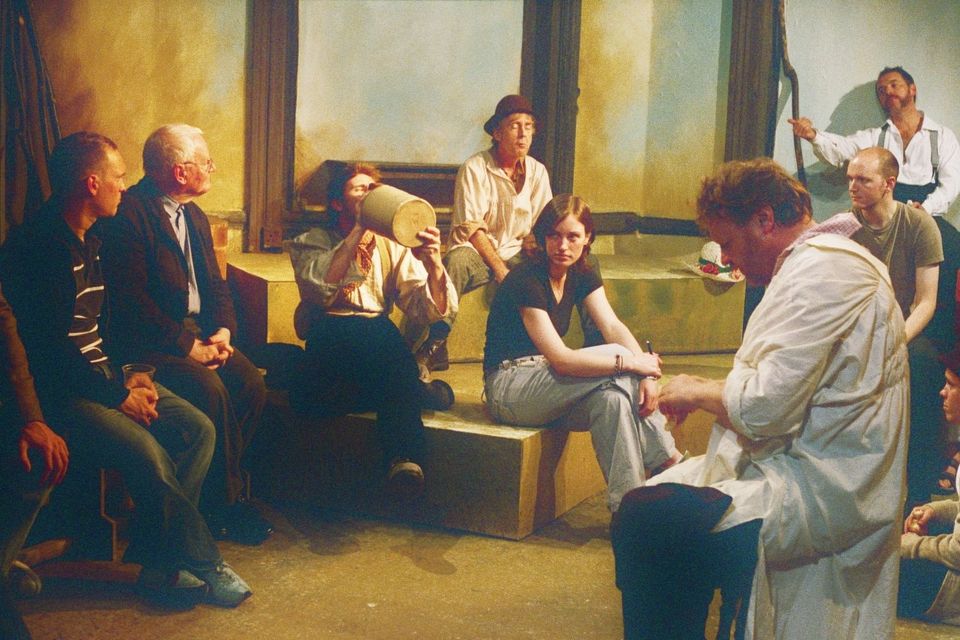

I’ve been fortunate to work on quite few good productions at the Finborough over the years and it’s probably why I keep coming back. The Finborough’s revival of Lark Rise to Candleford (adapted by Keith Dewhurst) was probably a favourite of mine, although it nearly finished me off at the time. It was an epic promenade, two play, cycle originally staged at The National Theatre. My two-level set used every conceivable corner of the space, we even had an actor enter through the tech box window and musicians in the stairwell outside the theatre! I did have a slightly wobbly moment after I put it all up and thought: ‘My God, have I produced something that is too over the top?’ The following day the cast walked into the space for the first time. There was a slight pause and one of them said ‘this is great! I haven’t felt like this since my Dad made me a tree house’, at that point I knew everything was going to be alright.

Shapeshifter, the producing company spearheaded by John Terry (Now artistic Director of The Theatre in Chipping Norton) and co-director Mike Bartlett (I think he went into writing...) received the Mark Marvin Rent Subsidy Award from the Peter Brook Awards, to assist towards the costs of mounting the production. On our acceptance of the award Lyn Gardener wryly commented “A promenade at the Finborough… Won’t that be more of a shuffle?” and she was right. The show was a bit like a lock-in at the local village pub with all the audience involved in the action in one form or another.

Image below: Lark Rise to Candleford (2005) A view from the wings… This sneaky shot of the audience was taken from off stage at the Final performance of the Finborough’s revival.

Image below: Lark Rise to Candleford (2005) An atmospheric shot of the set taken with some of the cast and creatives.

Fascinated to discover you have been involved with the Finborough Theatre as director as well as designer. What’s your first memory of the Finborough?

My first memory of the Finborough was designing a play called Charlie’s Wake. I think it was originally meant to be a Sunday/Monday show, but the production we were playing on top of fell through and we got upgraded at the last minute.

The main prop that I had to find was a coffin, as Charlie was stage managing his own wake to guilt trip his estranged daughter. Unfortunately, the director had cast an actor who had played a lot of rugby earlier in life and he had quite wide shoulders; far too wide to fit in a standard coffin, so I was dispatched to a coffin factory in Wimbledon in the hope that we would be able to get one for trade price. I was met by two men who checked their returns board for a spare coffin (Yes, there is such a thing!?) and they gave me a tour of the factory. At the end one of them said ‘We’ve made lots of coffins for film and TV over the years. I don’t know what they do with them all. We’ve done everybody… Tom Cruise… Jimi Hendrix...’ at which point the other one chipped in with, ‘No, he was one of the dead ones!’.

How did you first get involved as designer?

Initially I was going to study history at university, but I got offered a place to do an art foundation course at Wimbledon College of Art. I thought it might be fun to concentrate on art for a year before doing my degree, (this was in the last days before tuition fees came in and I recognise in retrospect how lucky I was). Well, I stayed on to do the Theatre Design degree course at Wimbledon. The history didn’t go away though, as every play is set in a period after all. One week I might be researching the Georgians and the next week skater culture. The performing arts is the closest I’ll get to time travel.

The other early influence on me as a designer was The Questors Theatre, in Ealing. The Questors is a long established amateur theatre in Ealing with two well-appointed stage spaces, I had been in the Youth Theatre there for years and it was only a matter of time before someone cottoned on to the fact I ‘did art’ and I was asked to design a set. My first ever design was for a production of ‘Godspell’. The sound and lighting designers were BBC staffers who each had about 30 years experience behind them and they were really supportive to this teenager who really didn’t know what he was doing. Wimbledon gave me the confidence to describe my creative ideas and at The Questors it was a case of ‘your budget is £700, the production starts on June 3rd… Good Luck!’ It gave me the resilience to produce theatre and gradually learn the practicalities of how to put on a production. Both of these qualities have stood me in good stead when designing productions at The Finborough.

How did the Directing come about?

The directing sort of happened by accident. I had got to the point where I had done every job in theatre above, on and behind the stage at some level or another except directing, so I persuaded Neil McPherson to give me a rehearsed reading to direct as part of the Finborough’s ‘Vibrant’ new play readings season, with the instruction ‘aim high, cast late’. I took him at his word and was terribly lucky when Alan Cox and Jasper Britton both said yes. If you have a cast who are instinctively ‘on the same page’ it is a question of guiding the production, exploring questions and providing clarity to the story. If your cast and production team are more disparate it can take a lot more energy and spadework to get the production to where it needs to be.

I have always had a soft spot for J B Priestley and there was a rarely revived play of his called Summer Days Dream, which I had read. It’s his take on a Midsummer Night’s Dream but set in a post-apocalyptic Britain that has lapsed back into a rural idyll. It has a lovely atmosphere and some great character dynamics. I suggested to Neil (Neil McPherson, Artistic Director of the Finborough) that we should do this one as part of our rare revival strand and he agreed. Originally, I was going to design it and we spent a while looking for a director. As time ticked on, I began to feel that I’d be really cross if I opened a season brochure for another theatre only to read that they had got in first. So, at that point I said I’d direct it myself. I was lucky to get a cast who balanced each other so well, with the late Kevin Colson as the patriarch of the Dawlish family, and a great creative and backline team. After the first night Tom Priestley approached me in the bar, shook my hand, and said ‘Well done, thank you so much for putting this production on, I saw the original in 1949 and never thought I’d get the chance to see it again’; after that I thought, I don’t really care what anyone else says about the production from here on, the author’s son likes it and that’s good enough for me.

Finally, have there been many laughs along the way?

Some truly bizarre things happen in the wonderful world of pub theatre. Usually having a bar downstairs is a positive asset, however, sometimes it can be a bit of a liability. I can particularly recall an incident that occurred during the run of a play about Wallis Simpson called ‘Untitled’. The pub management of the day had fallen into arrears and one night, just before the show was due to go up, a van arrived with some bailiffs to remove items from the pub. The bailiffs hadn’t quite twigged that the pub and the theatre are entirely separate entities, so they barged into the auditorium and prepared to start removing furniture and props that were on my set. Fortunately, we had Nichola McAuliffe in the cast who can be quite formidable when she chooses, even more so because she had personally lent prop items to the production! As the bailiffs upstairs retreated, the audience arriving downstairs were a little bemused to see the pub furniture being carried out in the opposite direction. If this scene wasn’t farcical enough, at that moment Margaret Beckett (At that point Minister of State for Housing and Planning) and her security detail arrived fresh from The House of Commons to see the play and found the pub in turmoil. A photograph of Margaret Beckett and the cast, Nichola McAuliffe and Patrick Ryecart, with folded arms staring at the camera was taken and the following day the saga warranted half a page in the Evening Standard.

Generally, my mantra is ‘keep the drama on the stage’, but it does from time to time have the unfortunate habit of seeping out in the most unexpected places. When working in fringe theatre I have found it is best to come armed with a sense of humour… and a mop!

ALEX MARKER BIOGRAPHY

Over the last 20 years Alex has designed for every type of venue from west end to fringe via, regional, touring theatre and even a converted mortuary.

As resident designer at the Finborough Theatre, Alex has designed some 30 productions over the last 20 years including: Lark Rise to Candleford, Red Night, Untitled, Me and Juliet, Death of Long Pig, The White Carnation (and transfer to Jermyn Street), Dream of the Dog (and transfer to Trafalgar Studios) and Plague Over England (and transfer to the Duchess Theatre) and most of James Graham’s early plays. At the Finborough he also directed Portraits by William Douglas Home and the first production for over 60 years of J. B. Priestley’s play, Summer Days Dream.

Other recent production designs include: The Odd Couple (Vienna’s English Theatre), The Firm, The Meeting (Hampstead Theatre), Harpy (Underbelly, Edinburgh and National Tour), Can’t Buy You Love, London Calling (Salisbury Playhouse), Bodies, What the Women Did, The Cutting of the Cloth, The Fifth Column and A Day by the Sea (Southwark Playhouse). Jeeves and Wooster in Perfect Nonsense and Sherlock Holmes and the Crimson Cobbles (The Theatre Chipping Norton and tours), Tape, My Real War 1914- ? (Trafalgar Studios).

Occasionally he makes elaborate scale model dioramas for Mischief Theatre’s ‘Goes Wrong’ TV appearances, but they always seem to end up ruining them. He is also director of the Questors Youth Theatre in West London.