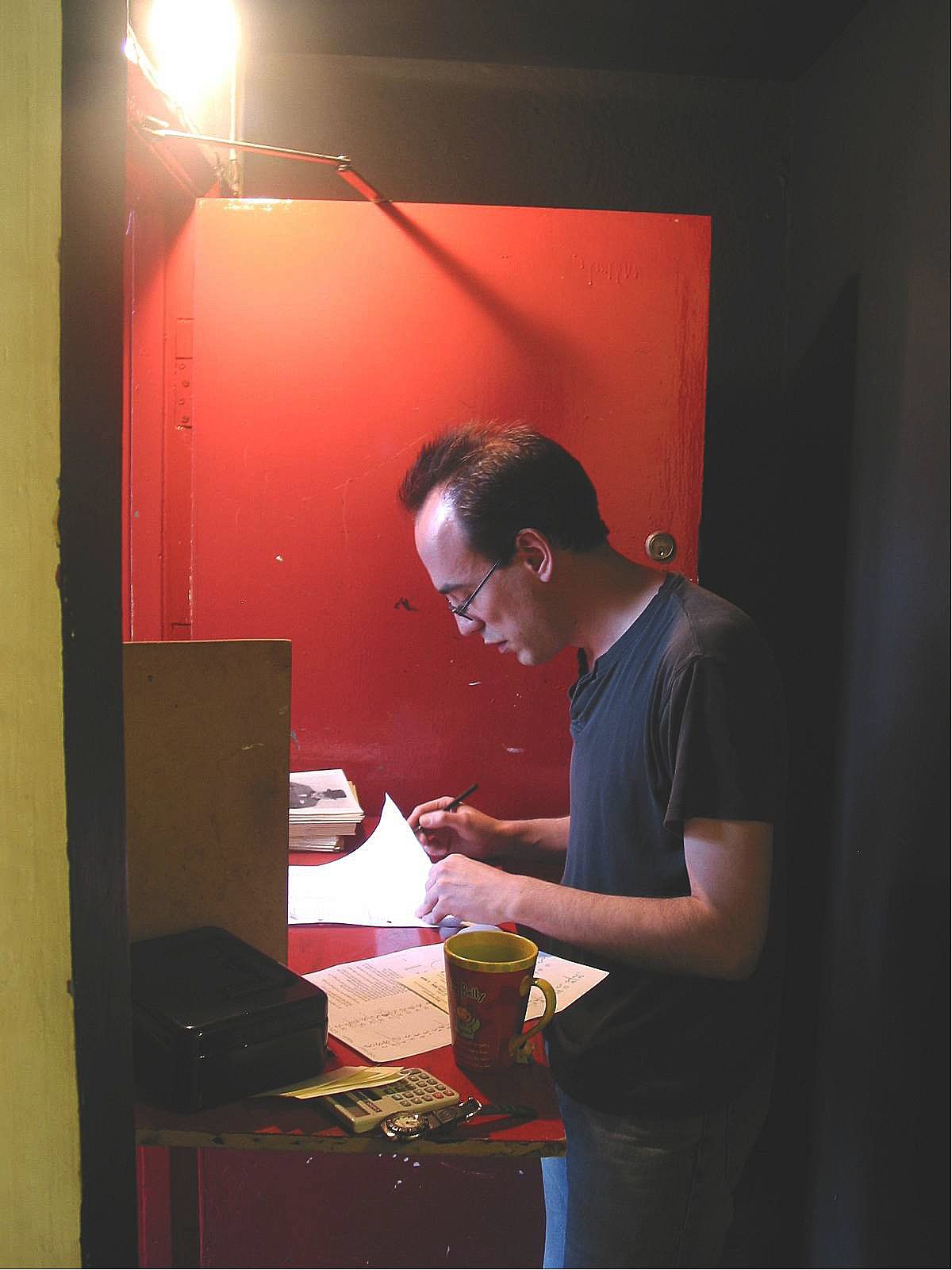

Neil McPherson is straight from another meeting and apologises for keeping me waiting. “Anj, artistic director from Australia over for a week … just wanted to talk about plays” he explains. Close to, the face is lean, pleasingly gaunt and somehow a little haunted. He is eager to get going with the questions.

Very few pub theatres are as well-known as the Finborough or have the international acclaim that it has achieved?

“Apparently … more famous in Toronto and Melbourne than here: Writer told me he went on holiday to New York, went to two theatres and they had our leaflet on their arts boards, he opened the New York Times and saw an advert for the Finborough.”

What has been the driving factor for such success?

“Reaching out and contacting other theatres. Putting them on our email list, sending them our plays and vice versa. We’re lucky to have the odd newly transferred play here. Ben Brantley from New York Times nearly always comes here when he comes over. We’re also keeping local links.”

What is at the heart of Finborough’s successful artistic programme/

“We do ‘brand-new’ or ‘so-old’ no one alive on the planet has seen it. We never do anything that’s been seen for the last 10 years in London. We can do the weird stuff that nobody else does”

McPherson is much funnier than expected and it’s easy to see he has a talent for story-telling.

“I was at this party and a rather bitter guy was bitching about every theatre in London … ‘Finborough do war, genocide, disease, politics, feminism, socialism... and camp cheesy musicals …’ I tapped him on the shoulder and said ‘yes we do!’”

What was his reaction?

“He looked embarrassed and sloped off. A lot of new plays will be raw and messy … usually they’ve got guts.”

My earlier interview of the day was with playwright Andrew Maddock and mentioning I was interviewing McPherson he immediately quipped “could I come with you, I’ve got a play to pitch to him”.

What makes a good Finborough writer? McPherson likes to keep it real:

“In the Vibrant new writing festival, we had a play set in an Israelis detention camp by a writer who was a guard in a detention camp. In the Syria conflict play, The Fear of Breathing (2012), the writer visited Syria three or four times.”

What have been the most controversial plays?

“Armenian Genocide – three death threats, and BNP play - bomb threat. It’s part of running a theatre. If you haven’t had a death threat in the last year you’re doing it wrong.”

What if I were to pitch a play?

“Uhm …?” He seems totally relaxed with no time pressures.

I pitch, and then tell him I’ve pitched “Ahh …” He’s sitting on his hands and doesn’t say anything. To cover an embarrassing moment, I quickly reassure him that I’ll send it to him. Then I tell him about his email to me after the last play I sent him which read (words to the effect): “Please don’t send another play for at least a year …”. McPherson shot back in his seat as though I’d punched him. “Oh, I’m so sorry”. Writers have to be able to laugh in the face of rejections and I found this much funnier than he did.

Are you still taking unsolicited scripts?

“Yes. We have a Literary department, plays are read by two readers and the literary manager before they come to me. Sometimes we get a great script but it’s not right for this particular theatre”.

Many artists want to work at the Finborough despite the fact that at this small 50 seat venue it isn’t possible to pay everyone all of the time. Unless it’s a tiny cast, productions don’t make any money. They would have to charge £200 a ticket to cover the cost of their larger productions.

What are the other reasons to work here?

“A stonking part, particularly if you’ve been in a long run musical and want to remind people that you can do straight acting too. Or for people who have had time off to have kids, it's a really good way to come back in. Casting directors come here, Nicholas Hytner (National Theatre) comes here to see shows, quite a lot of shows transfer. ‘Eyes Went Dark’ to Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh. ‘Operation Crucible’ is going to Sheffield Crucible and my play ‘It Is Easy to be Dead’ is probably going to the West End. “

I ask him about the backers?

“If you lose money here, you can make it up later on.” He adds: “We can do that mad big play that nobody else would touch because it is profit share, but its always about an equal balance between art and money. Money is still a huge consideration. We don’t ask actors to work for no money without thinking about it first.”

Many pub theatres are not guided by how much money can be made, but by their particular roles in the local or global community and by the stories they want to tell. So who are Finborough’s audience?

“What’s interesting is that we do new and old, so we get young under 25, totally multi-racial, and old white middle class over 60s. The audiences are starting to merge as people begin to trust us. One production, every single person under 30, multi-racial, right in the middle was a 65-year-old couple, she’d had her hair done to go to theatre, chatting away about her programme.”

How do you achieve that?

“Keeping it open and accessible. Sometimes telling things that nobody else touches, indigenous languages, playing in Welsh, and Scots Gaelic, old Scots (think Robert Burns).”

Is this job a mission, a vocation or a passion? McPherson seems momentarily stymied at this slightly more personal question. How does it work? What’s the balance?

“Kind of basically, you know, it’s not going to change the world but why - don’t - we - have a go. if some part of you didn’t think it would change the world you wouldn’t bother. Also its about giving different people a voice and a voice which nobody seems to touch.

He’s clearly more comfortable taking about plays:

“Old plays. Think it’s beyond arrogant to say somebody who lived in 1920s doesn’t have as much as we have to say about big human emotion. Love, jealousy, hate doesn’t change"

He also looks a little embarrassed when I tell him that I felt an emotional connection when I saw his play, It is Easy to be Dead. He modestly refers to himself as a writer who does “cobble jobs”.

“It’s researched. The Armenian play: Taken from about 5000 witness testimonies. Then Charles Sorley. Researched his work.” He adds gleefully “It’s out of copyright”.

McPherson has been avoiding my recurring questions about whether Finborough is outside of the mainstream?

“I say to all directors if you want to run the National in 20 years’ time, I want to do everything to help you to do that. With the deal that when they get there we can say we discovered them and they'll lend me lights! Everybody we get, gets stolen, poached by bigger companies with more money but obviously you really like when those people give credit for what you’ve done. James Graham is writing for the National and on Broadway and always credits Finborough.”

At the same time, you are giving opportunities to aspiring theatre professionals, just starting out, with internships, and new writing festivals.

All you can do is what you believe in and hope other people like it as well, you’ve got to listen to the gut.”

What are the stories you want to tell?

“I don’t know yet. I’ve got lots and lots of plays that I’d like to do. Whether they always work or not, each Finborough production has a voice of its own.”

How do you create your brand?

“With writers: Not imposing upon them. (You have to write in 25 hours, or in response to this other play, or newspaper item or song title.) Write about what their gut passion is about, likewise I don’t like directors in a hurry. Usually Oxbridge grads who would rape and kill their own grandmothers to run the National a year earlier. It’s about the art not the career. Career consideration is 3 % not 75%.”

Is all theatre political?

“Yep! … Even if it’s just ‘isn’t middle class life wonderful’.”

What are you most proud of achieving?

“Staying open”.

Finally, what’s the secret of your success?

“Finding good plays, doing them as well as humanly possible within the resources you have. For example, early on here I took a production of Hamlet because I had to pay (bills), and after that I’d rather not do a play just for the money, I’d rather close.”

He’s finished with a flourish. “That do you?” he says. I think it will.

Neil McPherson was chatting with Heather Jeffery, Editor of London Pub Theatres

@August 2016 London Pub Theatres Magazine Ltd

All rights reserved