BACK TO THE THEATRE

By Judi Bevan

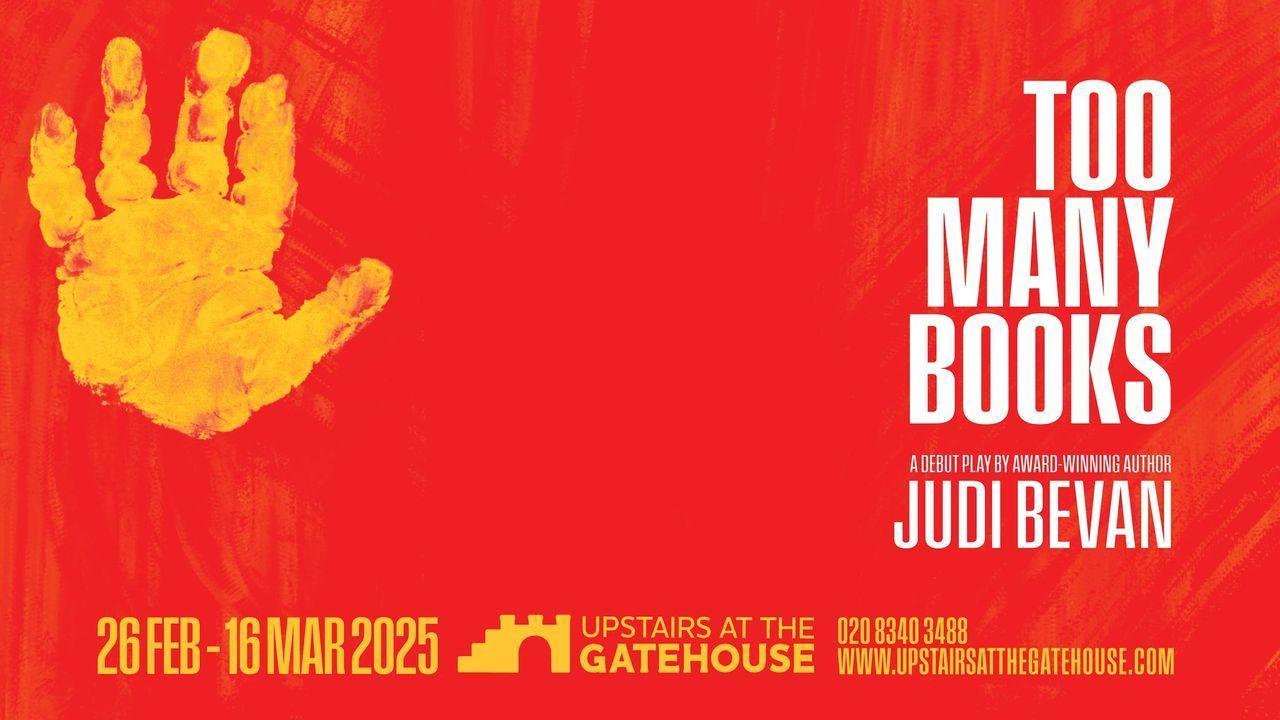

Award-winning journalist Judi Bevan's debut production, TOO MANY BOOKS comes to Upstairs at the Gatehouse in Highgate 26 Feb - 16 Mar. It sheds light on issues of identity, cultural displacement and the journey of parents seeking to adopt a child.

Published 16/1/2025

After a long career as a financial journalist and author of business books, I am not exactly sure what caused me to throw all the cards in the air and write a play for the theatre? Around 2017 I reflected on what to do next. We had adopted our daughter from China in 1998 and, while she was growing up, I had written four books including The Rise and Fall of Marks & Spencer as well as numerous articles.

Earlier, back in the late 1980s I had set off on my first venture into fiction with a novel called The Insiders set in the febrile world of the City of London during the takeover boom, a period of several financial scandals. To outsiders, the world of business may seem dull and grey but close up, as I was when working on the Sunday Times, Sunday Telegraph and Daily Mail financial pages, I discovered it was full of drama, intrigue, highs and lows. Success in business makes for fabulously rich heroes – or antiheroes depending on your point of view – such as Bill Gates and Donald Trump, while failure can result in bankruptcy or even a prison sentence.

I wrote The Insiders after attending a three-day course called Story Structure given by the now legendary Robert McKee, an American who had been a writer on the Columbo detective TV series among other things. Published by Piatkus, The Insiders achieved great reviews but modest sales. I went back to journalism. Thirty years later, I wanted to try my hand at drama. Perhaps that was no surprise. The theatre had been a constant in my childhood because my mother had been an actor and a director, with a theatrical career reaching back to her early childhood. On my father’s side, my grandmother filled her Manchester boarding house with touring theatricals.

I started playwriting classes initially at the City Lit in London with Jemma Kennedy, who a few years back presented Genesis Inc, her play about a couple’s trials with IVF, at the Hampstead Theatre. She was followed at the City Lit by the playwright and author, Conor Montagu, who then moved to head up the drama and fiction team at the Irish Centre in Hammersmith.

Growing up, some of my earliest memories are of the theatre because my mother directed plays for the rather grandly named Southgate Theatre Guild. She made her stage debut at four years old at the Alhambra in Glasgow and was a professional actress for 10 years as a young woman, playing, most memorably playing Peter Pan when she was barely 16 years old.

After the Second World War she found herself stranded in suburbia with a husband and young child – me, and began teaching adult drama to all-women evening classes. In those days, they would rehearse one-act plays and enter them in regional drama festivals, which were very popular in the fifties and sixties. In the school holidays, I would attend rehearsals and occasionally be roped in for a bit part as a child. During the festivals in places such as Felixstowe, I would be taken along on the coach. My mother’s groups invariably won the competition and sometimes won nearly every category – best drama, best play, best costumes, best this or best that. I have fond memories of the jubilant atmosphere on the coach home.

As the years passed by, my mother despaired at the lack of good-quality one-act dramas for women-only casts. So, while I was at school and my father was at work, she knuckled down and wrote one in longhand at our dining room table. Set in the dressing room of King Charles II’s mistress, Nell Gwynne, her play, A Kings Command, not only won her group many festivals but it sold to all-women groups overseas wherever English was the main language – mostly Commonwealth countries. The quarterly royalty cheques rolling in from her publisher, Samuel French, from such far-flung places as Australia, Canada and New Zealand gave her great joy. After her death, I asked Samuel French if it had my mother’s play in its archive because I did not have a copy. Not only did they produce one, they also handed me a small cheque covering unpaid royalties that had accrued over the previous two decades.

As a teenager I toyed with the idea of becoming an actress. My mother enrolled me in a group called The Junior Drama League, which met in London’s Fitzroy Square in the school holidays. I vividly remember going to a series of afternoon talks in the Criterion Theatre given by actors and directors. One afternoon it was the father-and-daughter team of Sir Michael and Vanessa Redgrave. When it was time for questions I piped up nervously: ‘How did you know if you should become an actor?’

Sir Michael was very clear. ‘Only do it if you can’t contemplate doing anything else,’ he said. I did not think that was me and if I was still in any doubt, it disappeared the following summer at a Junior Drama League course when, despite learning my lines thoroughly, I dried twice during the performance in front of the guest of honour, Dame Sybil Thorndike, a doyenne of British stage and screen. As well as having a distinguished theatrical career she had also starred with Sir Lawrence Olivier in the film versions of The Prince and the Showgirl and Uncle Vanya.

The following year, Judi Dench and John Stride regaled us with tales of appearing in Franco Zeffirelli’s stage production of Romeo and Juliet. Still in her early twenties, Dench was so funny and compelling that the three of us in the audience who were called Judy immediately started spelling our names with an ‘i’.

I began attending Conor Montagu’s playwriting classes about six years ago. My first effort was a play about the beginnings of Marks & Spencer. It felt promising as a drama because the founder’s son, Simon Marks, nearly lost control of the company early on after his father died and when he was only 19 – below the age of majority in those days. But despite this he succeeded in gathering just enough support from family shareholders to keep control. He became chairman at 21, a role he held for nearly 60 years, building M&S into one of Britain’s iconic retailers, now enjoying a renaissance. Somehow though, I struggled to finish it.

I then tried my hand at a dark play about a woman who unwittingly reports her son-in-law for child abuse, resulting in horrific consequences for her relationship with her daughter and granddaughter. It was based on a true story but, in the end, it just felt too dark.

Finally, I decided the best story was closest to home and I started working on the quest by a middle-class couple to adopt a baby daughter from China. Following several miscarriages and a failed attempt at IVF, they discover the path to adopting a young child in the UK is closed to anyone over 40 years old. In the 1990s, however, South American countries and China had unwanted babies available to be adopted by Westerners. The couple opt for China because it seemed that the process was much clearer than in South America, as the children were in orphanages, abandoned by their parents as a result of China’s one-child policy.

Combined with the Chinese desire for boy children, the policy meant that if a couple’s first child was a girl, she might be abandoned, sometimes just put in a field to die but often placed on the steps of a hospital, a temple or a children’s home or simply left in a public park or outside a bus or train station. Boys were more highly valued because when they married they would stay near their parents to work the land and look after them in their old age. Girls on the other hand would leave to live near their husbands’ families. In 1994, the Chinese Government responded to growing international condemnation of the consequences of its one-child policy by formalising a system of adoption for foreign nationals as long as they gained approval from the authorities in their own country to adopt – undergoing what is called a ‘Home Study’.

In my play, Too Many Books, the British couple’s misty-eyed optimism is soon shown to be naïve as they are mugged by the reality of inefficient bureaucracy and ill-trained social workers brimming with prejudice against them. The story is set between 1994 and 1996 and is partly informed by the problems we faced in adopting our daughter while also drawing on various sources ranging from fellow adopters to professionals in the adoption world.

One of the rules of authorship laid out by Robert McKee is ‘Thou shalt rewrite’, and Too Many Books has been through several versions. The benefit of a writing group is that scenes can be workshopped, then workshopped again. The only rule is that nobody should be cruel.

Times have changed in the adoption world since the mid-1990s and, in Britain today, would-be parents are increasingly allowed to adopt children of a different ethnicity and class to their own. Even so, last year, 2024, there were more than 80,000 children in care in Britain and only 3,000 deemed by social workers to be suitable for adoption. There is still enormous scope for improvement.

Judi Bevan is the author of Too Many Books, which will be performed at Upstairs at the Gatehouse, Highgate, from 26 February - 16 March. Information and bookings